On February 11, Head of School Geoff Wagg gave a virtual State of the School address to the Waynflete community from the Klingenstein Library in the Lower School. Geoff reviewed the past year, outlined the elements that will help shape the future, and discussed the issues we must grapple with in preparation for the next academic year.

Antonio Rocha brings storytelling talents to Waynflete to help celebrate Black History Month

In celebration of the art of storytelling and Black History Month, we were happy to have Antonio Rocha join us for a Lower School Assembly. This event was made possible by the Class of 1970 Guest Speaker and Visiting Artist Fund.

2020 Festival of Student-Written Plays

Student in Waynflete’s Performing Arts program recently performed three student-written plays to a small live audience and via live stream. Read descriptions of the plays below, then click the links to watch!

Starry Night in EC

When the EC Loons returned from winter break, they dove into a study of Vincent van Gogh’s artwork. After looking closely at a number of his paintings, the children showed heavy interest in “Starry Night.” They looked at other artists whose work was inspired by Starry Night, then decided to make their own Starry Night Environment in a corner of their classroom.

The children worked on painting the swirly sky, the moonlit town, stars, moon, and the tall tree on large pieces of cardboard. They assembled all the pieces, then added a night sky light. The product is a beautiful rendition of Starry Night that the children can now use as a quiet corner in the classroom for reading or meditation.

10 Tips for Guiding Your Child Through the Middle School Years

By Divya Muralidhara (Middle School Director)

The years of early adolescence are full of change and challenge. At Waynflete, we see this juncture as one of profound growth and discovery. Our students are leading community drives, working with younger peers, mentored by Upper School students, and otherwise immersed in the curriculum. We emphasize skill-building and perspective during the three years. Our faculty are invested in Middle School and have broad experience in supporting students and families, and we offer the following advice as you anticipate your child’s entry into Middle School:

EC–5 art show

Early Childhood–Grade 5 artwork is currently on view in the Klingenstein Library.

The Loon Pod in EC have been looking closely at the artwork by Vincent Van Gogh. While studying “Starry Night,” the students were interested in the swirls in the night sky. After watching videos of other artists making their own “Starry Night”-inspired art, they did their own! Students used shaving cream and water colors to create swirls of color and pressed paper down on top to make a print.

LitMag – Inauguration Edition!

Take a look at a special issue of LitMag, created in honor of the inauguration of President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris.

Identity, Diversity, Justice, and Action

As a Lower School, we are committed to making Waynflete a place of belonging for all students, families, and staff. In our continuing work on anti-bias and anti-racist teaching, we know it takes intentional work to reach this goal. It requires us to uncover and challenge our own biases, and to include diverse voices in our curriculum.

8 Essential Building Blocks of a Kindergarten Program

By Jess Keenan (K-1 faculty)

After eight years of teaching at Waynflete, I know that kindergarten is not just about getting students ready for “school.” It’s about laying a foundation for a love of learning that students will take with them through the rest of their school years and beyond. Parents are sometimes unsure about which aspects of a kindergarten program are most important. Here are eight essential building blocks of a strong kindergarten to consider when you’re looking for a program that is right for your child.

LitMag – Fall 2020

Click here to check out the latest issue of LitMag!

Artwork above: “Being a Child” by Selina He

7 Ways To Get Kids Excited About Science

By Carol Titterton (6-12 science chair)

1. Start with teachers who have real-world experience

Teachers who have worked or earned degrees in scientific fields are more apt to be genuinely interested in their subject. Waynflete’s faculty, which includes former nuclear engineers, wildlife ecologists, physicists, microbiologists, and biotech researchers, are more likely to introduce field work, numerous labs, and opportunities to work with scientists in their classes. The result? Greater student enthusiasm and engagement.

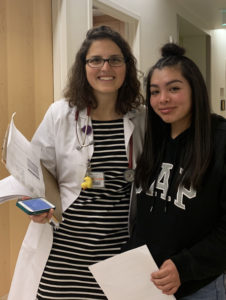

As a schoolteacher and pediatrician, Emily Frank ’04 puts lessons learned at Waynflete to good use

Speak with Emily Frank and you will quickly learn this: she likes to wear many hats.

After four years in the orbit of teachers including Wendy Curtis, Carol Titterton, and David Vaughan, Emily had become passionate about science. During the summer before her freshman year in college, a scholarship at the Maine Medical Center Research Institute provided her with an initial taste of medicine. It was a thrilling experience—“I couldn’t believe that people got paid to do research for a living,” she recalls. After considering a degree in astronomy, Emily chose to major in cell biology after matriculating to Dartmouth College. But as she progressed through the program, she found herself increasingly drawn to the school’s education department. Emily was attracted by the idea of a career that was “somewhere on the science-education spectrum,” and that path began to coalesce into a plan: she would start out as a high school science teacher (to learn effective teaching skills) with the hope of someday becoming a college biology professor.

After four years in the orbit of teachers including Wendy Curtis, Carol Titterton, and David Vaughan, Emily had become passionate about science. During the summer before her freshman year in college, a scholarship at the Maine Medical Center Research Institute provided her with an initial taste of medicine. It was a thrilling experience—“I couldn’t believe that people got paid to do research for a living,” she recalls. After considering a degree in astronomy, Emily chose to major in cell biology after matriculating to Dartmouth College. But as she progressed through the program, she found herself increasingly drawn to the school’s education department. Emily was attracted by the idea of a career that was “somewhere on the science-education spectrum,” and that path began to coalesce into a plan: she would start out as a high school science teacher (to learn effective teaching skills) with the hope of someday becoming a college biology professor.

Emily restructured her junior year at Dartmouth to participate in a mentored teaching program in the Marshall Islands during the winter semester. “It was a life-changing experience,” she recalls, adding that it included “some of the most purposeful and happiest days of my life.” She employed a pedagogical method that will be familiar to most Waynflete faculty members: if a teacher concludes that some aspects of the curriculum are no longer relevant to the students, the teacher can change it. In their science class, students wanted to learn about reproductive issues, diabetes, and the effects of drugs on the brain. “That was what was relevant to them, so that’s what I taught them about,” she says.

Back at college, Emily’s experiences in Dartmouth’s science labs had led her to become disillusioned with academia. She still wanted to teach science, but not at the college level. “I knew my education at Waynflete had been special,” she says. “It was the standard for the quality of education that all kids should receive, regardless of race, income, or life circumstances. What I was coming to better understand, though, was how much a child’s education can depend on their zip code.” After graduating, she resolved to shore up her teaching skills by working with Teach For America (TFA).

During her two-year tenure at TFA, Emily taught middle school life sciences in Vallejo, a community in San Francisco’s North Bay area. Vallejo had been a thriving port city in the 1970s before undergoing economic collapse (around the time that Emily arrived, the municipality had declared bankruptcy due to rising personnel costs and declining revenue from a housing slump). It was a jarring transition for a 23-year-old who had spent most of her life in Brunswick, Portland, and Hanover, but she continued to build confidence in her ability to connect with children. “I just loved getting kids excited about science and seeing the light bulb go on,” she says. School administration didn’t appeal as a career path—she wanted to influence children’s lives in a hands-on way, particularly when she had the opportunity to design curriculum—but she felt she still needed additional tools. Her education journey was to continue in an unorthodox way: she would train to become a medical doctor.

Emily earned her MD from Tufts University. Tufts’ “Maine Track” program is grounded in a community-based curriculum that enables future physicians to work at clinical sites throughout the state (students spend the majority of their time in Maine). “From the very beginning, I was so impressed with their philosophy of education,” she says. “Although my degree is from Tufts, I really learned how to be a doctor from physicians throughout the state of Maine.”

Emily earned her MD from Tufts University. Tufts’ “Maine Track” program is grounded in a community-based curriculum that enables future physicians to work at clinical sites throughout the state (students spend the majority of their time in Maine). “From the very beginning, I was so impressed with their philosophy of education,” she says. “Although my degree is from Tufts, I really learned how to be a doctor from physicians throughout the state of Maine.”

Partway through her training—a period she recalls as “drowning in biochemistry”—Emily was still driven by the desire to work with students. Along with two TFA alumni, she co-founded Health Impact Partnership in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood in Boston. “When I was in Vallejo, I had really wanted to start a program where kids could identify the health issues that mattered to them and feel supported in taking action to bring about change,” she says. “This was the way to do it.”

There are many programs around the country in which medical school students visit local communities and educate residents on a variety of topics. Emily’s unique idea was to build her new program on a foundation of participatory action research, an approach that, according to the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, “aims to improve health and reduce health inequities through involving the people who, in turn, take actions to improve their own health.” Emily and her team worked in a diverse school district that was home to many new immigrants. “We wanted to create something that lifted students up by encouraging them to identify what mattered to them,” she says. “The high school students developed a needs assessment and interpreted the data. Our contribution as medical school students was to support them each step of the way.” The program also provided valuable opportunities for future doctors to strengthen their communication skills in different cultural environments.

Nutrition was top of mind for students in the community. While many were eating healthily at home, few knew how to cook. The students in the program identified high school seniors as a group that was particularly at the risk of suffering from poor nutrition after leaving school. The kids in Emily’s program designed, printed, and distributed a healthy-eating cookbook. “This was a beautiful example of how students’ voices and opinions are so valuable,” she says.

Returning to California

Although Emily was interested in psychiatry and emergency medicine, she decided to specialize in pediatrics. “Pediatricians have a real focus on prevention and advocacy, which resonated with the type of work I wanted to do,” she says. She returned to the Bay Area to complete her residency, which focused on leadership for advancing health equity. As before, Emily helped launch a youth participatory action research project in the Oakland Unified School District, building a series of student lessons that highlighted careers in the healthcare industry. “What was the most fun for me was wearing so many hats,” Emily says. “Designing the curriculum, training adult facilitators, guest teaching, supporting students—I was using all my skill sets, and I loved that feeling.”

Emily became a near-full-time teacher and a part-time physician. Working as a clinical pediatrician in the evenings, on weekends, and during the summer, she began teaching at Life Academy, an Oakland public school serving students in grades 6–12. Founded in 2001, Life Academy seeks to “dramatically interrupt patterns of injustice and inequity for underserved communities in Oakland” by preparing students for challenging careers in health and bioscience. Over the course of their studies, students build an in-depth understanding of public health, health literacy, and health advocacy. It’s a hands-on, experiential program, with kids doing everything from creating educational videos on the Covered California healthcare exchange to establishing bone marrow registration drives in an effort to decrease racial disparities in the registry. Early in the pandemic, COVID-19 infection rates rose rapidly in the neighborhood. In response, students created infographics in a variety of languages to encourage mask use. “To see students feel empowered in the face of national bewilderment, and to provide them with a sense of agency, was really gratifying,” Emily says. “Many of the problems that stem from lack of health literacy or investment are fixable if we enlist our young people to help solve them. Adults don’t have all the answers.”

Diversity in the healthcare industry

It is an unfortunate fact that in many healthcare institutions, racial diversity exists only in lower-level positions. The more education is required, the more homogeneous the workforce becomes. The cycle can be self-reinforcing. When students in predominantly Black and Hispanic communities interact with primarily white doctors, it is difficult for those students to imagine a future career in advanced healthcare. Emily sees this effect come into play as the seniors in her classes begin to consider colleges. “I ask them whether they’ve considered applying to CalTech, MIT,” she says. “They tell me, ‘Oh, I can’t get in.’ I tell them that it’s not for them to decide. That’s for the schools to decide.” Life lessons from Waynflete—finding the courage to knock on what appear to be closed doors and, in the face of rejection, learning to get back up and try again.

There are industry pipeline programs, but most start at the college level—too late, in Emily’s estimation. The high school programs that do exist often target the same small group of students who are clearly performing at a high level. “So many kids just need the flame to be ignited,” she says. “That’s what interests and excites me—to go below the surface and reach out to those students. There are many kids who walk the fine line between tremendous success and awful consequences. They have so much potential— how much of that potential gets used depends on the support they get in middle and high school. I’m really interested in exposing young people who are at risk to opportunities and helping them use their tremendous potential for whatever they want.”

That exposure includes inviting as many guests of color as possible into the classroom, including doctors, scientists, and other healthcare professionals. “I know that as a white teacher, I can never have the same impact on kids as a teacher of color in their community,” Emily observes. “There are all kinds of cultural nuances that I am oblivious to. Every young person should grow up believing that they are agents of their own future. So I try to ask myself: ‘What I can do, in an ally position, to make sure that my students see the full range of opportunities that can be open to them?’”

That exposure includes inviting as many guests of color as possible into the classroom, including doctors, scientists, and other healthcare professionals. “I know that as a white teacher, I can never have the same impact on kids as a teacher of color in their community,” Emily observes. “There are all kinds of cultural nuances that I am oblivious to. Every young person should grow up believing that they are agents of their own future. So I try to ask myself: ‘What I can do, in an ally position, to make sure that my students see the full range of opportunities that can be open to them?’”

Dreaming it

Emily’s belief in the importance of listening to kids and lifting up their voices is rooted in her memories of Waynflete. “Two of the most important things I learned are that your voice matters and that you can do anything,” she says. “If you can dream it, and if you can identify resources you can draw on, you can ultimately do it.” Waynflete teachers are often the standard by which she judges her success in the classroom today. They also inspire specific pedagogical approaches. Debba Curtis, one of Emily’s favorite teachers, had students complete “SARs” (summary, analysis, reaction) for every primary document and article read in class. “I now teach my ninth graders how to SAR,” she says. “How do you take a piece of literature or something in the news and determine what it’s about, why it matters, and how you feel about it?”

Effective time management is essential for someone balancing two demanding professions. “It starts with

being clear about what you value—what matters most to you—and what you’re willing to compromise on or let go of,” she says. “While there are some things I have to give up, doing so lets me do the work I value most.” Emily loves to hike, cook, dance, and do yoga. Even when her schedule becomes extreme, exercise is non negotiable. “I couldn’t manage without it,” she says.

Like those of most doctors and teachers, Emily’s working life over the past year has been dominated by the pandemic. Looking longer term, she plans to continue working on what has emerged as a specialty for her: creating high-impact experiences that have positive effects on both students and the healthcare industry. She hopes to expand her work at Life Academy to the entire Oakland school district (the pandemic has demonstrated that it is possible to conduct the program virtually) and get greater buy-in from hospitals and other organizations that are eager to diversify their workforces and build pools of future talent.

When asked what counsel she would give to today’s high school students, Emily reflects on advice that she received from a friend years ago: explore as much as you can, and in the process of doing so, observe what brings out “the best you.” “While pediatrics allows me to wear my preventative and advocacy hats, it also gives me the opportunity to make silly faces, or sing a song, or be ridiculous with a child,” she says. “I love that pediatrics brings this out in me. It’s the same with teaching. The people who know me best have spent time in my classroom. This is where ‘me’ comes out to the maximum.”

9 Proven Ways to Get Kids to Succeed in and Love Middle School

By Betsy Langer (Middle School history)

Middle school parents know that it’s just not realistic to expect their sixth-graders to sit still, stay quiet and focused, and listen to a teacher for 50 minutes. At Waynflete, we know that middle schoolers need a special kind of classroom—one based on realistic academic, social, and behavioral expectations about where they are developmentally. They also need teachers who love teaching kids their age, who find ways to manage a classroom without saying “shush,” and who teach the essential skills that help students organize their work, their thinking, and mostly importantly, themselves.

2020 Maine Chinese Speaking Contest

Waynflete’s Ellie Simmons ’21 and Liam Slocomb ’22 recently competed in the 2020 Maine Chinese Speaking Contest. They each prepared a short (less than five minutes) speech, which they delivered to a panel of judges. Ellie took first place while Liam took second in the intermediate category.

Congratulations to Ellie and Liam!

Waynflete hosts 24-Hour Theater Fest

Waynflete theater hosted the 5th annual 24 Hour Theater Fest—Virtual Edition. Nine schools attended, twelve plays were written overnight, and 27 students were present on Saturday to bring the plays to life on Zoom. The quality of the writing and acting was impressive. Thank you, Kate, Jack, Orion, Ransom, and Claire for representing Waynflete so well! And thank you to students and directors from Bonny Eagle, Central, Casco Bay, Cheverus, Kennebunk, Morse, Scarborough, and Portland High Schools!

7 Things to Consider When Choosing the Right Pre-K For Your Child

By Bob Mills, Debbie Rowe, Gretchen Schaefer (EC faculty)

Children who are three or four years old often find the transition from home to school easier if the environment, curriculum, and adults are engaging. At its best, school can harness young children’s vast curiosity, receptivity, and energy while nurturing their love of learning and school.

There are many fine pre-K programs in Greater Portland. How do you know which program will be right for your child and your family?

Here are seven important things to look for as you visit preschools:

Color Theory Sea Turtles

In conjunction with their study of marine life, 2-3 students made observational paintings of sea turtles. Students began by drawing hexagons, incorporating them into shell patterns. Using reference materials, artists made drawings and mixed primary colors of tempera paint to complete the compositions.

The drawings are currently on display in the Klingenstein Library Gallery.

NAIS Student Leadership Conference

Six Waynflete Upper Schools students will attend the National Association of Independent Schools’s virtual Student Diversity Leadership Conference (SDLC) from December 1–4.

The four-day event is a multiracial, multicultural gathering of high school student leaders from across the U.S. and abroad. SDLC focuses on self-reflecting, forming allies, and building community. Led by a diverse team of trained adult and peer facilitators, participating students develop cross-cultural communication skills, design effective strategies for social justice practice through dialogue and the arts, and learn the foundations of allyship and networking principles. In addition to large group sessions, SDLC “family groups” and “home groups” allow for dialogue and sharing in smaller units.

7 Ways to Reduce Middle Schooler Stress and Improve Their Ability to Learn

By Kate Ziminsky (Middle School seminar instructor)

Life can feel overwhelming to the middle schooler who is navigating longer periods of focused attention on academics, working to balance extracurricular activities with homework, and beginning to chart a course toward adulthood and self-reliance—all while a large volume of highly stimulating, provocative information streams in at high speeds, through myriad devices, at every moment of the day. To empathize with the challenges that your child faces at this stage in their development, it is important for you to learn more about the middle-school brain.

Metamorphoses

Congrats to the cast and crew of Metamorphoses who, in the time of COVID, rose to the challenge of putting on a socially distanced play about love and relationships! While some family members were able to attend—a rare celebration of live performing arts—students also mastered the technology to live stream the performance using multiple cameras. Way to go!