Beyond APs

Beyond APs

How Waynflete Cultivates Academic Excellence

A typical school wants its students to score well on standardized tests, which in turn causes the school to encourage teachers to march through a certain volume of content in each class period. If a student asks a question because she is curious about something, she threatens to take the class off course. Teachers learn to squelch such questions so the class can stay on task. [This] discourages inquiry in favor of simply shoveling content with the goal of improving test scores. And when children have lost their curiosity…they tend to remain incurious for the rest of their life.

This matters. You can sometimes identify a bad leader by how few questions they ask; they think they already know everything they need to. In contrast, history’s great achievers tend to have an insatiable desire to learn. In his study of such accomplished creative figures, the psychologist Frank Barron found that abiding curiosity was essential to their success; their curiosity helped them stay flexible, innovative, and persistent.

– David Brooks, “How Ivy League Admissions Broke America,” The Atlantic, December 2024

Originally established by the College Board in the 1950s to provide college-level classes to high school students, Advanced Placement (AP) courses are today regarded by some parents as synonymous with academic rigor. Waynflete has taken a different approach to designing its Upper School curriculum, however, prioritizing intellectual exploration over a standardized syllabus. The school’s faculty and administrators contend that academic excellence is cultivated through personalized, immersive learning rather than a one-size-fits-all model. This philosophy aligns with a growing number of independent schools, including Phillips Academy (one of the founding institutions of the AP program), Georgetown Day School, Milton Academy, and Phillips Exeter Academy, that have moved away from the AP model entirely.

Moving Beyond “Teaching to the Test”

“Independent schools are uniquely positioned to rethink curricula in ways that emphasize creativity and inquiry,” according to a 2019 report from the National Association of Independent Schools. “Colleges are looking for students who can think critically, connect ideas, communicate effectively, and tackle real-world problems—not just memorize facts for a test.” A Washington Post analysis, authored by the heads of eight independent schools, highlighted a growing shift away from AP courses. The authors argue that AP courses, while historically seen as the pinnacle of high school rigor, often prioritize standardized content at the expense of creativity and interdisciplinary learning that independent schools like Waynflete aim to cultivate.

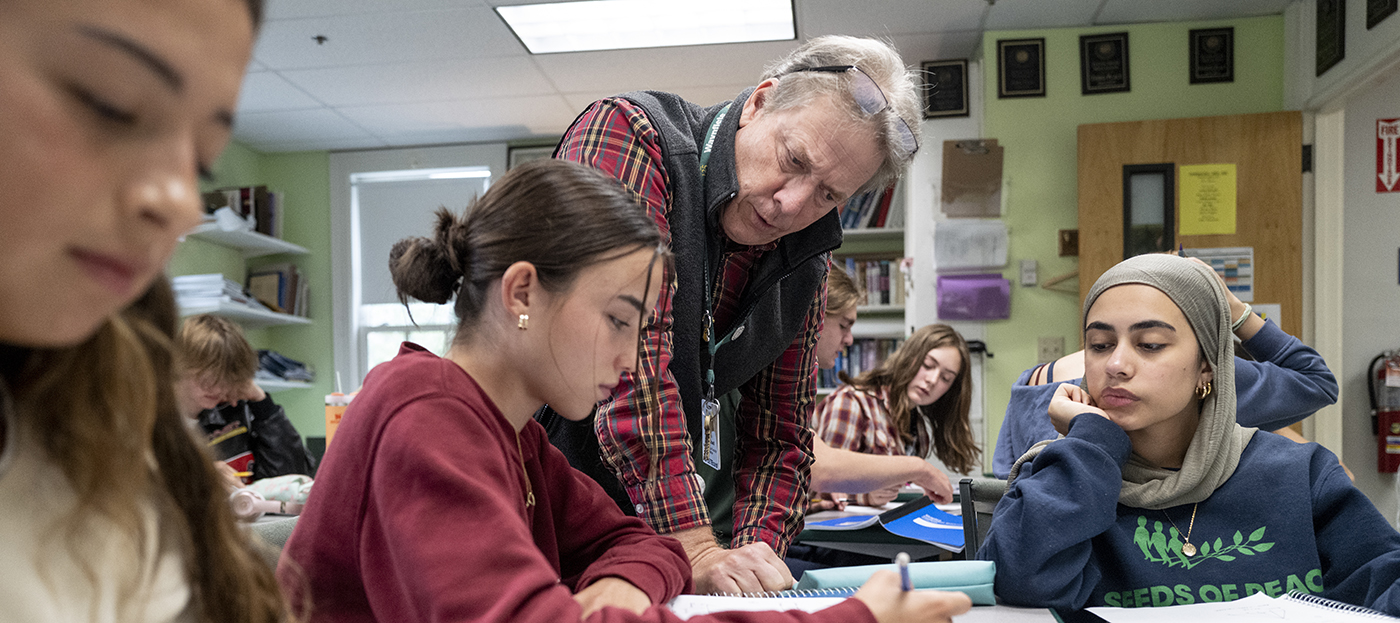

Waynflete mathematics teacher Jim Deterding captures the challenge of AP-focused teaching: “You’ll never hear a Waynflete teacher say, ‘I’m sorry, but we just have to move on’,” he says. “What we offer is pacing for mastery, not for coverage—and it all comes from a place of personal passion, not a set of external standards.” Freed from the rigid timeline of preparing students for a single high-stakes exam, Waynflete educators can adapt to their students’ interests. This flexibility enables teachers to explore complex topics in depth, fostering academic growth and—more importantly—sparking genuine enthusiasm for learning. “There’s no question that academic rigor is stronger at Waynflete without AP classes,” says Deterding’s colleague, math department chair Cathy Douglas. “Teachers can push kids in ways that stretch them, instead of following a scripted curriculum that isn’t theirs.”

The freedom to design their courses allows Waynflete teachers to incorporate broader, interdisciplinary approaches. Science teacher Wendy Curtis describes how her students spend weeks designing and troubleshooting their own experiments, an approach that encourages the development of problem-solving skills that are essential to real-world scientific inquiry. “We wouldn’t be able to devote that kind of time if we had to stick to a strict AP schedule,” Curtis explains. “It allows time for deeper exploration in the classroom. AP courses, on the other hand, emphasize familiarity and memorization.” Waynflete Head of School Geoff Wagg highlights the difference this approach makes in the classroom: “Wendy’s Astrophysics course is one of many here at the school that is equivalent to a college class. These courses have all the rigor you would expect, and they’re taught by passionate professionals. This would be challenging to reproduce this context in an AP environment.”

Maren Cooper ’20, who is studying biochemistry at Bowdoin College, echoes this sentiment. “My favorite units tended to be those where the teachers were personally passionate about the subject, which I believe was only possible because they didn’t have to teach to the test,” she says. “It made it such an enjoyable and engaging environment in which to learn.”

John Radway, who chairs Waynflete’s English department, stresses another advantage of the school’s approach: the ability to design courses that reflect both teacher expertise and student curiosity. “This is a place that gives you the freedom to explore deliberately and with passion,” he says. “That freedom allows students to find and pursue their own rigor while being guided by teachers every step of the way. It’s about giving students an intellectual backdrop and exposing them to horizons beyond what they’ve encountered so far.” The emphasis on depth over breadth is particularly notable in the humanities, allowing for thematic explorations that include the literature of genocide, postcolonial African literature, and medieval studies—subjects unlikely to find a place in an AP curriculum. “Waynflete’s ethos is ‘learn to learn’,” says Curtis. “You don’t learn by memorizing facts and details for an AP US History exam. You learn by digging into documents and understanding different perspectives.”

Upper School Director Asra Ahmed underscores the importance of tailoring education to the community and students. “The APs represent a prescribed formula that a group of educators somewhere in the country determined is the way students should be taught,” she says. “That curriculum isn’t responsive to our students, our community, or our history. By letting teachers design their own curricula, we’re able to focus on what our kids need in a given year. If we want to spend more time on a topic that resonates deeply, we can do that.”

Colleges Appreciate—and Reward—Depth

Independent schools that forego AP courses offer students a distinct advantage when it comes to college preparation. Waynflete’s college counselors emphasize that colleges evaluate students in the context of their school’s offerings. John Thurston explains, “What colleges want to see is that students are taking the most rigorous courses their school offers—and that’s exactly what our students are doing.” Mesa Robinov adds that over the past five years, approximately three quarters of Waynflete graduates gained admission to their first- or second-choice colleges. “College admission officers look at our profile and see a school with an 11-to-1 faculty-to-student ratio,” she says. “These are not students who are going to hide in lecture halls. They’re prepared for intensive, seminar-based classes.”

Wagg affirms this point, explaining that colleges value the rigorous preparation students receive in non-AP curricula. “What colleges want to see—particularly the most selective ones—is that the student is stretching themselves academically and that they’re well-prepared to succeed. They don’t penalize them because they’re not taking APs,” he says.

Beyond college admissions, Waynflete alumni frequently cite their writing and analytical skills as a key strength in higher education and beyond. Radway notes, “Our students graduate able to adapt to different intellectual challenges. That flexibility is their greatest asset.” This adaptability serves them well in college classrooms and future careers. “When I catch up with recent graduates, they often tell me how surprised they were to discover that their classmates, who were the highest achieving students at their high schools, struggled to write,” says Robinov.

Cooper’s experience bears this out. “A lot of my classmates in my first-year writing seminar at Bowdoin seemed to struggle with how to construct an argument and write a paper,” she recalls. “I never had any difficulty with that. I would even pull up some of my essays from Waynflete English classes to help me remember how I had crafted an argument, and I still regularly refer back to my high school lab reports.”

The Case for Independent Thinking

Critics of the AP model argue that it often prioritizes surface-level mastery over deeper engagement. Wagg describes the challenges of AP-based learning: “If you were to interview a group of students who are taking several AP courses, they would tell you that there’s so much work to do. That ‘grind’ often feels overwhelming. They have so much to memorize—it becomes less about the subject matter and more about just checking boxes.”

Ultimately, Cooper believes that Waynflete’s approach fosters a genuine love of learning that serves students well beyond high school. “When you’re in a classroom where the teacher loves what they’re doing, and can connect the subject matter to your interests, it fosters an amazing learning environment,” she says. “I gained a passion for knowledge at Waynflete, and I learned how to think. I feel like that’s way more valuable than any AP score would be.”